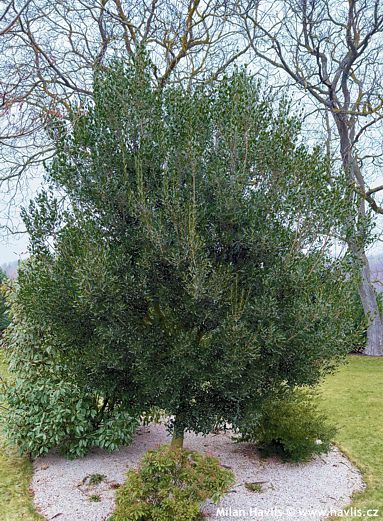

Phillyrea latifolia large-leaved mock privet, green olive tree

Phillyrea

The genus Phillyrea belongs to the olive family (Oleaceae) and includes only two species of evergreen shrubs and small trees, primarily distributed around the Mediterranean. It was scientifically described in 1753 by Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) in his seminal work Species Plantarum, where he openly acknowledged that phillyreas were not newly discovered plants from distant expeditions but woody species long familiar to the European landscape and culture. The father of modern botany, as Linnaeus is often called, merely gave them systematic names and classification. In recent decades the genus has returned to the attention of gardeners and botanists in connection with climate change. Slightly rising temperatures, later onsets of winter, abrupt weather swings and, above all, long‑term declines in precipitation create conditions in which some traditional woody species reach the limits of their tolerance while others, previously overlooked, begin to thrive unexpectedly. Phillyreas are among those that cope with these changes calmly and without obvious signs of stress — and remain evergreen.

Phillyrea latifolia originates from somewhat milder but still very dry parts of the Mediterranean, where it functions as one of the key structural elements of the native vegetation. It occurs from the Iberian Peninsula across southern France and Italy to the Balkans, often on rocky slopes, in open woodlands and at the margins of macchia, where it forms a transition between open scrub and forest. Unlike the narrow‑leaved phillyrea (Phillyrea angustifolia), which is a specialist of extreme drought and poor soils, P. latifolia appears more balanced and less narrowly adapted – a species capable of occupying a broader spectrum of natural habitats within the Mediterranean landscape.

The origin of its scientific name reaches deep into Greek mythology. The story tells of a sea nymph named Φιλύρα (Philyra), so beautiful that the god Cronus fell madly in love with her. To avoid discovery – since he already had a wife – he transformed himself into a stately stallion and seduced her in that guise. From their union was born the centaur Chiron, half man and half horse, later one of the most important centaurs in Greek myth. Philyra, ashamed and distraught, begged the gods to free her from human form; they granted her plea and transformed her into a tree – the phillyrea – a name that the genus still bears.

Large-leaved mock privet is a low, very bushy evergreen tree with such a picturesque, dense crown that it has earned the English nicknames broccoli tree or green olive tree. Its leaves are opposite, broadly elliptic to ovate, typically 3–6 cm long, very stiff and leathery, with a glossy, dark green surface and shallowly toothed margins. This combination of thick tissues and gloss enables the plant to manage water efficiently and to reflect a large portion of incoming sunlight – a typical adaptation of Mediterranean woody plants. Compared with P. angustifolia, the leaves present a more refined appearance, and the overall habit is firmer and more tree‑like. In late spring small, inconspicuous flowers appear, followed by small, hard fruits that complete the plant’s modest but botanically pure silhouette.

In its native range, it was traditionally valued as an exceptionally reliable woody plant, providing shade, shelter for small wildlife, stabilizing slopes, and helping to retain soil in places where other trees failed. There it typically reaches heights of 6 to 10 metres with a very similar spread, while in the cooler regions of Central Europe it usually remains up to half that size. It tolerates a wider range of sites than its narrow‑leaved relative, responds better to seasonal weather fluctuations and can prosper where the soil is somewhat deeper and more fertile. This adaptability makes it a natural transitional species between open macchia and forest. In gardens it functions as an outstanding solitary specimen with clear architectural structure, bringing a Mediterranean character without the need for intensive care. Nevertheless, it can be pruned and shaped - multi‑stemmed forms in particular look very impressive.

Phillyrea latifolia primarily requires a well‑prepared site: a fertile but very well‑drained soil in which water does not stand in winter. Although it can cope with deeper clay subsoil, the upper soil layer must not remain waterlogged, otherwise root rot may occur. After planting, keep the soil evenly moist for the first couple of months; once the plant is established, greatly reduce or stop watering altogether – phillyrea is accustomed to getting through the summer on natural rainfall alone. It performs best in full sun but tolerates light partial shade. It is advisable to plant stronger, more mature specimens so they better withstand the first winter; reported hardiness is approximately −24 °C (USDA zone 4), though this depends on provenance and plant age. It is not prone to major diseases or pests, and pruning is minimal – shearing and shaping is best done in midsummer. With proper establishment, P. latifolia becomes a long‑lived, calm and exceptionally reliable woody plant.

Last update 17-10-2019; 25-01-2026