Perovskia atriplicifolia 'LITTLE SPIRE' Russian sage

Perovskia

The genus Perovskia originates from the arid regions of Central Asia, naturally thriving on open steppes and rocky slopes: for example, in Tibet it inhabits high plateaus at elevations reaching up to 2400 meters above sea level. It's commonly referred to as Russian sage and sometimes even Russian lavender. Botanically, it's classified as a subshrub — a growth form somewhere between a perennial and a shrub — and thanks to its exceptional tolerance of drought, severe frost, intense sunlight, heat, and poor soils, it's widely used in modern prairie-style plantings. Strictly speaking, however, it’s a steppe plant, the distinction being purely geographic: its native range is in Asia, not the American prairie, though it shares similar ecological traits.

The name Perovskia honours Vasily Alekseyevich Perovsky (1795–1857), a prominent Russian general and governor of the Orenburg region. Although he wasn’t a botanist, his military and diplomatic campaigns in Turkestan enabled numerous scientific expeditions, which gained access to the region’s previously unexplored flora. In recognition of this, the genus was named after him by German botanist Carl Anton von Meyer in 1841, who described the plant while conducting botanical research in the area.

In horticulture, Perovskia atriplicifolia, also described by Meyer in the same year, has become the most prevalent species. It is bred through both selections and hybridization with related species, most often P. abrotanoides, P. angustifolia, or P. scrophulariifolia, which contribute traits like finer foliage, a more compact habit, or slightly different inflorescence architecture. The widespread popularity of perovskia was significantly boosted by American grower David Salman, who selected it for the dry climate conditions of the southwestern United States.

For taxonomic enthusiasts and detail lovers, there’s another intriguing twist: based on molecular analyses, the plant was officially reclassified in 2017 from the genus Perovskia into Salvia, now bearing the name Salvia yangii. This name honours Chinese botanist Chang Y. Yang, a specialist in sage phylogeny. Despite the official renaming, most gardeners and nurseries still refer to it as Perovskia atriplicifolia — not only for practical reasons, but also for the charisma embedded in its original name. Its longevity, low maintenance requirements, and ornamental beauty have secured its place in many garden designs, gracing both private landscapes and public plantings with equal elegance.

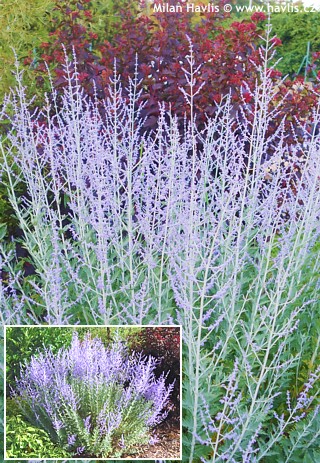

Little Spire is a smaller, more compact cultivar of Russian sage, first introduced in 1995. Its flowers resemble tiny slippers — vivid inky violet-blue in colour — and emerge from deep purple buds that begin forming as early as June. While peak blooming occurs in the second half of summer, the richly colored buds make the plant visually appealing from early in the season. After flowering, the purple calyces remain, giving the plant a long-lasting ornamental effect — often well into October.

The flowering stems are airy and richly branched, and each year they produce an increasing number of blooms, turning the plant into a vibrant violet cloud by August. The deciduous leaves start out bright silvery-grey and mature to light grey-green. On this cultivar, they are notably narrow with subtle marginal serration. The stems and foliage contain a strongly aromatic essential oil reminiscent of sage. The plant typically reaches 60–70 cm in height and eventually spreads to a similar width.

Perovskia is easy to grow. It tolerates almost any soil — preferably lean and well-drained — as overly moist conditions in winter can cause root rot. Once well established, it copes superbly with drought. For strong growth and abundant flowering, prune it back in early spring by one third to one quarter of the previous year’s branches. If the plant is weak, it can be cut down to around 5 cm, which promotes new shoots and thus more blooms. It is fully hardy to approximately –30 °C (USDA zone 5), with some sources claiming tolerance down to –34 °C. It’s well suited to year-round cultivation in outdoor planters, just ensure excellent drainage as excessive moisture can cause yellowing (chlorosis) and leaf drop.

Last update 18-07-2008; 15-07-2025